“Remember Jesus Christ, risen from the dead, the offspring of David, as preached in my gospel, for which I am suffering, bound with chains as a criminal. But the word of God is not bound! Therefore I endure everything for the sake of the elect, that they also may obtain the salvation that is in Christ Jesus with eternal glory. The saying is trustworthy, for:

If we have died with him, we will also live with him;

if we endure, we will also reign with him;

if we deny him, he also will deny us;

if we are faithless, he remains faithful—

for he cannot deny himself.”

(II Timothy 2:8-13)

I am generally of the opinion that most novel interpretations of Scripture which cut against the grain of the received wisdom of the ages are simply mistaken. The majority voice in biblical scholarship over time carries tremendous weight with me, and I think it ought to with most Christians (especially with individualistic Protestants such as myself). I believe that 98% of the Bible has been fantastically understood throughout church history by the teachers and theologians of the church, and our greatest need is almost never brand new interpretative insight into God’s Word. Rather, it is the grace and faith to obey it, live it out, and apply it faithfully and creatively in each successive generation through the Spirit. I deeply resonate with C. S. Lewis’ frustration with the “chronological snobbery” that seems to be a peculiar ailment of the snobbish Western academy of late.

Nonetheless, I present here a dissenting voice on the standard scholary consensus–as well as the widespread popular understanding–concerning 2 Timothy 2:13, in which Paul writes that “if we are faithless, he [God] remains faithful, for he cannot deny himself.” The mainstream explanation of this passage, as represented both in the critical commentaries and in the “common sense” construal of most English readers today, is that Paul is encouraging young Timothy in his ministry by assuring him of God’s constant mercy (“He remains faithful”), even in the face of the anguished struggles and occasional failures in the life of believers (“even if we are faithless”).

Allow me to state right from the outset that such a sentiment is not only orthodox and consistent with the entire tenor of the gospel of grace as found in the New Testament, but it is beautiful and compelling and worth reminding ourselves of daily as we continue to wrestle with the effects of the sin that remains in our hearts. Yet I am also convinced that inferring such a perspective from 2 Timothy 2:13 is a classic example of drawing out the right doctrine from the wrong text, for such a construal simply is not anywhere close to Paul’s intended meaning here. I offer five reasons in defense of my exegetical unbelief:

1.) It breaks the parallelism of the four stanzas in 2:11-13, the first two of which are indisputably positive statements of reassurance for believers. The third (“if we deny him, he also will deny us”, echoing Matthew 10:33 and other similar utterances of Jesus) is surely a negative warning directed to confessing Christians. It makes a whole lot of sense, a priori, if the fourth stanza completes the pattern by repeating or elaborating upon such a warning. I am convinced that this is exactly what it does.

2.) The use of “unfaithful” (apistos/apisteo) language in Paul is much more definitive and unyieldingly negative than the positive interpretation of 2:13 allows for. To be “faithful” or “unfaithful” in Paul’s use of this vocabulary always draws a tight, clean distinction between believers and unbelievers. To interpret it here as referring to authentic Christians who are merely struggling with old sinful habits would be utterly out of step with every other Pauline usage and waters down Paul’s typical employment of the word. “Unfaithful” consistently refers either to outright unbelievers or to fallen, lapsed confessors who have decisively turned away from the Lord and are no longer walking with Him.

3.) The positive interpretation of 2:13 does not fit the context of the immediately surrounding flow of thought. Paul, as he has been wont to do structurally throughout the letter, is exhorting Timothy to not be ashamed of the gospel but instead to join with him in suffering for it. As in several other places in 2 Timothy (see 1:15-18, 3:8-11, and 4:6-10), Paul expounds upon his call for faith-filled obedience in Timothy’s life by appealing to both positive and negative personal examples that illustrate the consequences of our potential responses to such weighty injunctions. Here, both Jesus and Paul serve as models who first suffered in weakness, but who were later vindicated in their missions by God’s power–a pattern that the first two couplets in 2:11-12 expound upon.

And immediately after this ancient hymn, Paul goes on to mention Hymenaeus and Philetus in 2:14-19. Apparently these two men were formerly teachers and leaders in the church, but have turned away from the faith (that is, they are “faithless”) and are even denying the future resurrection from the dead of believers. Notice the eerily similar and intentional parallel to the latter two (negative) couplets of 2:12-13 in 2:18-19: “They have swerved from the truth, saying that the resurrection has already happened. They are upsetting the faith of some. BUT God’s firm foundation stands, bearing this seal: “The Lord knows those who are his,” and, “Let everyone who names the name of the Lord depart from iniquity.” Verse 18 highlights a recent example of those who have denied the Lord and been faithless to Him. Verse 19 illustrates that in spite of this faithlessness, the Lord yet remains faithful–that is, He knows who truly belongs to Him, and imposters who arise within the people of God are not a just cause for our trust in the Lord to be shaken. Instead, they will be denied in turn.

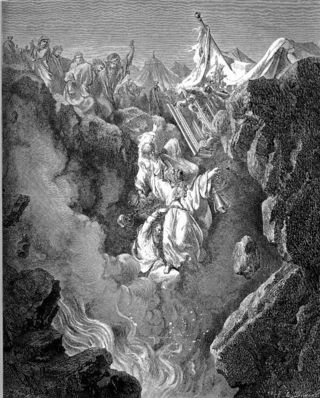

The allusion to Numbers 16:5 (LXX) strengthens the likelihood of this interpretation. In the story of Korah’s rebellion, a comparable historical situation is described. An influential leader within Israel has turned away from the Lord, bringing judgment upon himself. In spite of the panic this brings about for God’s people, the confident answer from Moses calms their fears: “In the morning the Lord will show who is His.” Korah’s faithlessness has not nullified the faithfulness of God. He actually does not belong to Him, and his apostasy has manifested this state of affairs. Even here, the Lord’s act of judgment is not a denial of His holiness and promises, but instead their fulfillment.

4.) The word “deny” (arneomai) is found both before and after the statement “if we are faithless, he remains faithful”, grounding these statements with the assurance that the Lord cannot “deny” Himself. While not conclusive as an argument, this leads me to think that Paul’s thought remains in the same conceptual category in these latter two couplets that are linked by the word “deny”–that is, they both function as warnings.

5.) There is a striking and almost completely overlooked parallel to 2 Timothy 2:13 in Romans 3:3-4: “What if some were unfaithful (apisteo)? Does their faithlessness [apistia] nullify the faithfulness [pistis] of God? By no means! Let God be true though every one were a liar.” Not only is the language incredibly resonant with that of 2 Timothy 2:13, but the context is as well. In Romans 3:1-8, Paul briefly introduces a heartbreaking theme that he will later develop in Romans 9-11: namely, that ethnic Israel’s unexpected and tragic rejection of the Davidic Messiah does not invalidate God’s faithfulness to His promises and His people; the word of God has not fallen to the ground empty (9:1-6). All this in spite of the tremendous turmoil and erosion of confidence in God’s faithfulness that it apparently caused for many in the early church.

Years later, having learned this lesson well and at enormous personal cost to himself, Paul sorrowfully yet boldly reminds Timothy that God’s demonstration of His own goodness and righteousness are not thwarted by even the most shocking and heartbreaking defections from the faith within the confessing people of God. The Lord knows who belongs to Him, and He will remain faithful regardless of those who turn away from Him. This is the meaning of 2 Timothy 2:13.

I know that in my own life some of the most faith-testing and gut-wrenching experiences I have endured as a Christian have come through the Hymenaeus’s and Philetus’s (2:18), the Phygelus’s and Hermogenes’s (1:15), and the Demas’s (4:10) in my own life, those who have consciously turned away from Jesus after what seemed to be genuinely good beginnings in their spiritual devotion to the Savior. 2 Timothy, as even a casual glance at the letter demonstrates, is filled with such bitter disappointments in Paul and Timothy’s Christian relationships. The leadership in the Ephesian church has apparently crumbled from within, abandoning the orthodox faith and thus fulfilling Paul’s earlier warning to the church in Ephesus (Acts 20:28-32). Yet Paul’s faith is still solid, for the Lord remains faithful in spite of it all. He cannot deny Himself. This is the ultimate basis of Paul’s confidence. And this divinely-constructed foundation possesses a permanent stability, whatever personal betrayals or rejections we meet with from those who formerly sang and worshiped and prayed with us among God’s people. It is a good, albeit harsh lesson to learn before such times arrive for us. Even now, may we all begin to lay down deep roots into the faithfulness of God, a faithfulness which remains even in the face of the worst, most unexpected human faithlessness.